Pluto Is Now a Planet Again

For 76 years, Pluto was the beloved 9th planet. No ane cared that it was the runt of the solar organization, with a moon one-half its size. No 1 minded that it had a tilted, oval-shaped orbit. Pluto was a weirdo, just it was our weirdo.

"Children identify with its smallness," wrote science author Dava Sobel in her 2005 bookThe Planets. "Adults relate to its … existence equally a misfit." People felt protective of Pluto.

So it was perhaps non surprising that there was public uproar when Pluto was relabeled a dwarf planet xv years ago. The International Astronomical Matrimony, or IAU, redefined "planet." And Pluto no longer fit the nib.

This new definition required a planet to do three things. First, information technology must orbit the dominicus. Second, it must have plenty mass for its own gravity to mold it into a sphere (or close). 3rd, it must have cleared the space around its orbit of other objects. Pluto didn't pass the third examination. Hence: dwarf planet.

"I believe that the conclusion taken was the correct i," says Catherine Cesarsky. She was president of the IAU in 2006. She'south currently an astronomer at CEA Saclay in French republic. "Pluto is very different from the viii solar-system planets," she says. Plus, in the years leading upward to Pluto's reclassification, astronomers had discovered more than objects beyond Neptune that were similar to Pluto. Scientists either had to add many new planets to their list, or remove Pluto. It was simpler to just requite Pluto the kick.

"The intention was not at all to demote Pluto," Cesarsky says. Instead, she and others wanted to promote Pluto as one of an important new class of objects — those dwarf planets.

Some planetary scientists agreed with that. Among them was Jean-Luc Margot at the University of California Los Angeles. Making it a dwarf planet was "a triumph of science over emotion. Scientific discipline is all nigh recognizing that before ideas may have been wrong," he said at the time. "Pluto is finally where it belongs."

Others accept disagreed. Planets should not have to clear their orbits of other debris, argues Jim Bell. He'south a planetary scientist at Arizona Land University in Tempe. An object's ability to bandage out droppings does not just depend on the trunk itself, Bell says. Then that shouldn't disqualify Pluto. Everything with interesting geology should be a planet, he says. That manner, "it doesn't affair where you are, it matters what you are."

Pluto certainly has interesting geology. Since 2006, we've learned that Pluto has an atmosphere and maybe fifty-fifty clouds. It has mountains made of h2o ice, fields of frozen nitrogen and methane snow-capped peaks. Information technology even sports dunes and volcanos. That fascinating and active geology rivals whatsoever rocky world in the inner solar arrangement. To Philip Metzger, this confirmed that Pluto should count as a planet.

"At that place was an immediate reaction confronting the dumb [IAU] definition," says Metzger. He's a planetary scientist at the University of Central Florida in Orlando. But science runs on evidence, not instinct. So Metzger and colleagues have been gathering evidence for why IAU's definition of "planet" feels so incorrect.

The ascension and fall of Pluto

For centuries, the word "planet" was much more inclusive. When Galileo turned his telescope on Jupiter in the 1600s, any large moving body in the sky was considered a planet. That included moons. In the 1800s, when astronomers discovered the rocky bodies now called asteroids, they called those planets, too.

Pluto was seen as a planet from the very beginning. Amateur astronomer Clyde Tombaugh first spotted it in telescope photos taken in January 1930. At the fourth dimension, he was working at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Ariz. Upon his discovery, Tombaugh rushed to the observatory director. "I accept constitute your Planet X," he declared. Tombaugh was referring to a ninth planet that had been predicted to orbit the sun across Neptune.

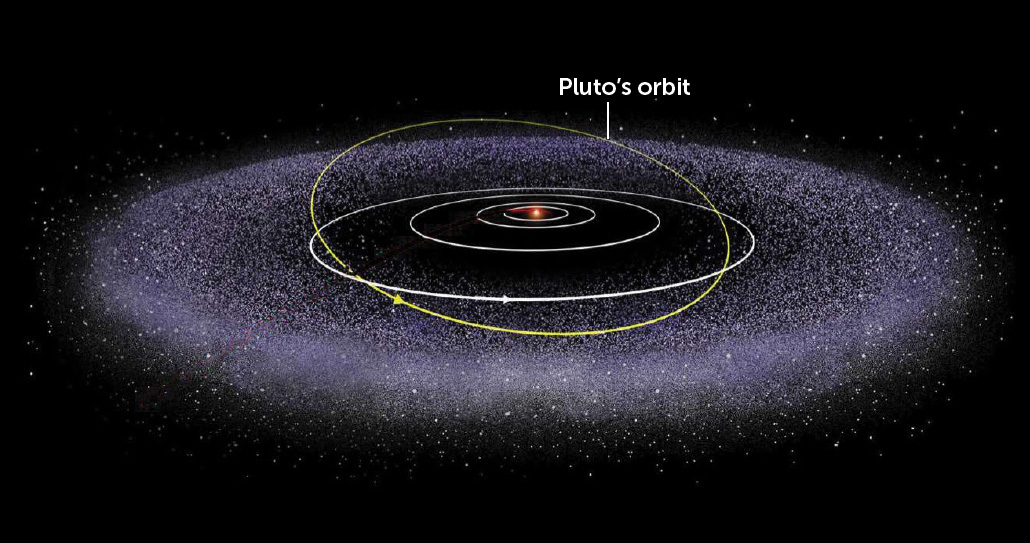

But things got weird when scientists realized Pluto wasn't alone out at that place. In 1992, an object about a tenth as wide as Pluto was seen orbiting out across it. More than 2,000 icy bodies have since been plant hiding in this frigid outskirt of the solar arrangement known as the Kuiper (KY-pur) Chugalug. And there may be many more still.

Finding that Pluto had and then many neighbors raised questions. What did these foreign new worlds have in mutual with more familiar ones? What set them autonomously? Of a sudden, astronomers weren't sure what truly qualified equally a planet.

Mike Brownish is a planetary scientist at the California Institute of Engineering science in Pasadena. In 2005, he spotted the first Kuiper Belt body that appeared larger than Pluto. Information technology was nicknamed Xena, in honour of the TV showXena: Warrior Princess. This icy body was left over from the formation of the solar system. If Pluto was the ninth planet, Brown argued, then surely Xena should exist the 10th. Just if Xena didn't deserve the championship of "planet," Pluto shouldn't either.

Tensions over how to categorize Pluto and Xena came to a head in 2006. The drama peaked at an IAU meeting held in Prague, the capital of the Czech Republic. On the concluding 24-hour interval of the Baronial meeting, and later on much heated debate, a new definition of "planet" was put to a vote. Pluto and Xena were accounted dwarf planets. Xena was renamed Eris, the Greek goddess of discord. A plumbing fixtures title, given its role in upsetting our concept of the solar system. On Twitter, Brown goes by @plutokiller, since his research helped knock Pluto off its planetary pedestal.

Messy definitions

Right abroad, textbooks were revised and posters reprinted. Simply many planetary scientists — especially those who study Pluto — never bothered to change. "Planetary scientists don't utilize the IAU'due south definition in publishing papers," Metzger says. "We pretty much just ignore it."

In part, that might be sass or spite. Simply Metzger and others think there's besides good reason to pass up IAU'south definition of "planet." They make their case in a pair of papers. One appeared as a 2019 report inIcarus. The other one is due out shortly.

For these, the researchers examined hundreds of scientific papers, textbooks and messages. Some of the documents dated back centuries. They bear witness that how scientists and the public have used the word "planet" has changed many times. And why was often not straightforward.

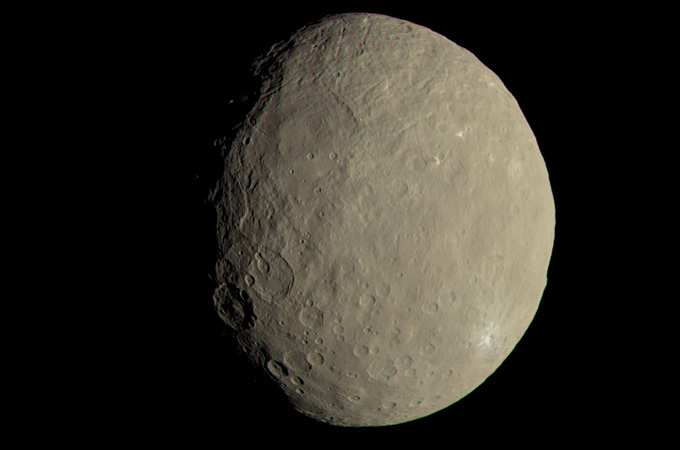

Consider Ceres. This object sits in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Like Pluto, Ceres was considered a planet after its 1801 discovery. Information technology'south often said Ceres was lost its planethood after astronomers found other bodies in the asteroid belt. Past the cease of the 1800s, scientists knew Ceres had hundreds of neighbors. Since Ceres no longer appeared special, the story goes, it lost its planetary title.

In that sense, Ceres and Pluto suffered the aforementioned fate. Correct?

That'due south not the existent story actually, Metzger's team now reports. Ceres and other asteroids were considered planets — albeit "minor" planets — well into the 20th century. A 1951 article inScience News Lettersaid that "thousands of planets are known to circle our sun." (Scientific discipline News Alphabetic character afterward became Scientific discipline News, our sister publication.) Most of these planets, the magazine noted, were "small fry." Such "baby planets" could be as modest every bit a city block or as wide as Pennsylvania.

The term "minor planets" only barbarous out of fashion in the 1960s. That's when spacecraft got a closer expect at them. The largest asteroids however looked similar planets. Nearly small ones, nevertheless, turned out to exist weird, lumps. This provided evidence that they were fundamentally different than the bigger, rounder planets. The fact that asteroids didn't clear their orbits had nix to do with their name change.

And what about moons? Scientists called them "planets" or "secondary planets" until the 1920s. Surprisingly, people didn't stop calling moons "planets" for scientific reasons. The modify was driven by nonscientific publications, such equally astrological almanacs. These books employ the positions of celestial bodies for horoscopes. Astrologers insisted on the simplicity of a limited number of planets in the heaven.

But new data from infinite travel later brought moons dorsum into the planetary fold. Starting in the 1960s, some scientific papers over again used the word "planet" for objects orbiting other solar system bodies — at least for some large round ones, including moons.

In short, the IAU definition of "planet" is simply the latest in a long line. The give-and-take has inverse meanings many times, for many different reasons. So there's no reason why it couldn't be changed once again.

Real-world usage

Defining "planets" to include certain moons, asteroids and Kuiper Belt objects is useful, Metzger now argues. Planetary scientific discipline includes places like Mars (a planet), Titan (one of Saturn's moons) and Pluto (a dwarf planet). All these places take extra complication that arises when rocky worlds get big enough to go spherical. Examples of that complication bridge from mountains and atmospheres to oceans and rivers. Information technology'south scientifically useful to have an umbrella term for such circuitous worlds, Metzger says.

"We're not claiming that we have the perfect definition of a planet," he adds. Nor does Metzger recall anybody need prefer his. That's the mistake the IAU made, he says. "We're saying this is something that ought to be debated."

A more inclusive definition of "planet" might as well requite a more accurate concept of the solar organization. Emphasizing eight major planets suggests they boss the solar system. In fact, the smaller stuff profoundly outnumbers those worlds. The major planets don't even stay in fixed orbits over long time-scales. Gas giants, for instance, have shuffled around in the by. Viewing the solar organization as only eight unchanging bodies may not do that complication justice.

Dark-brown (@plutokiller) disagrees. Having the gravitational oomph to nudge other bodies around is an important feature of a planet, he argues. Plus, the eight planets clearly dominate our solar organization. "If you dropped me in the solar system for the first time, and I looked around … nobody would say anything other than, 'Wow, there are these eight — choose your word — and a lot of other petty things.'"

Ane common argument for the IAU definition is that it keeps the number of planets manageable. Can y'all imagine if in that location were hundreds or thousands of planets? How would the average person keep rail of them all? What would we print on lunch boxes?

Merely Metzger thinks counting simply eight planets risks turning people off to the rest of space. "Back in the early 2000s, at that place was a lot of excitement when astronomers were discovering new planets in our solar system," he says. "All that excitement ended in 2006."

However many of those smaller objects are still interesting. Already, there are at least 150 known dwarf planets. Most people, however, are unaware, Metzger says. Indeed, why do we demand to limit the number of planets? People can memorize the names and traits of hundreds of dinosaurs or Pokémon. Why not planets? Why non inspire people to rediscover and explore the space objects that virtually appeal to them? Maybe, in the end, what makes a planet is in the eye of the beholder.

Source: https://www.sciencenewsforstudents.org/article/pluto-dwarf-planet-definition-iau-astronomy

0 Response to "Pluto Is Now a Planet Again"

Post a Comment